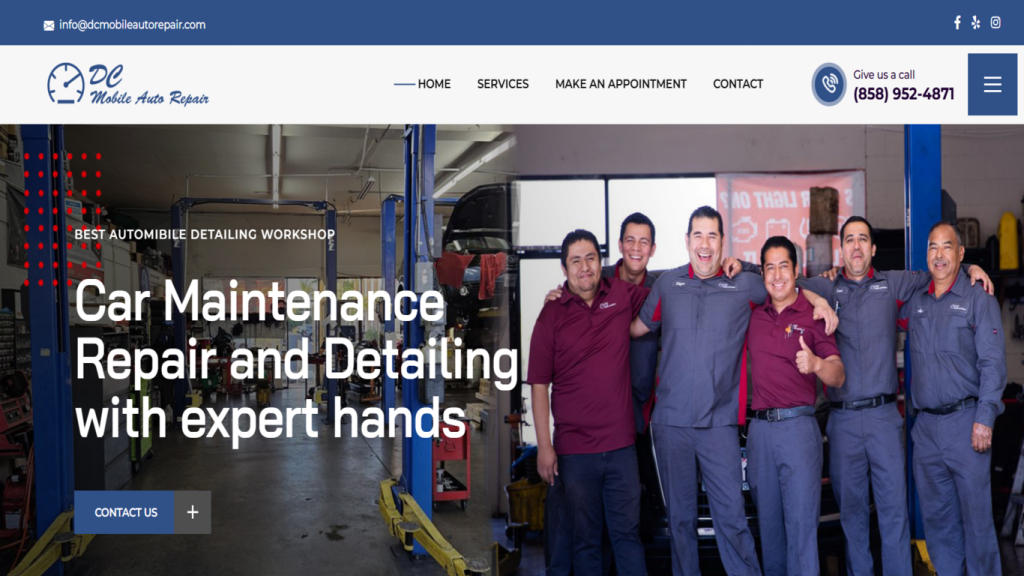

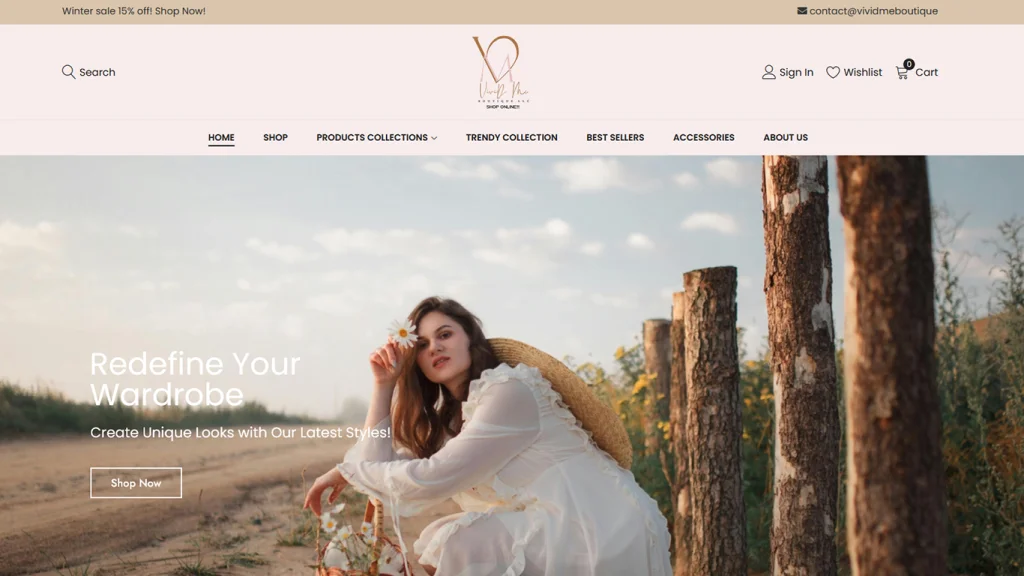

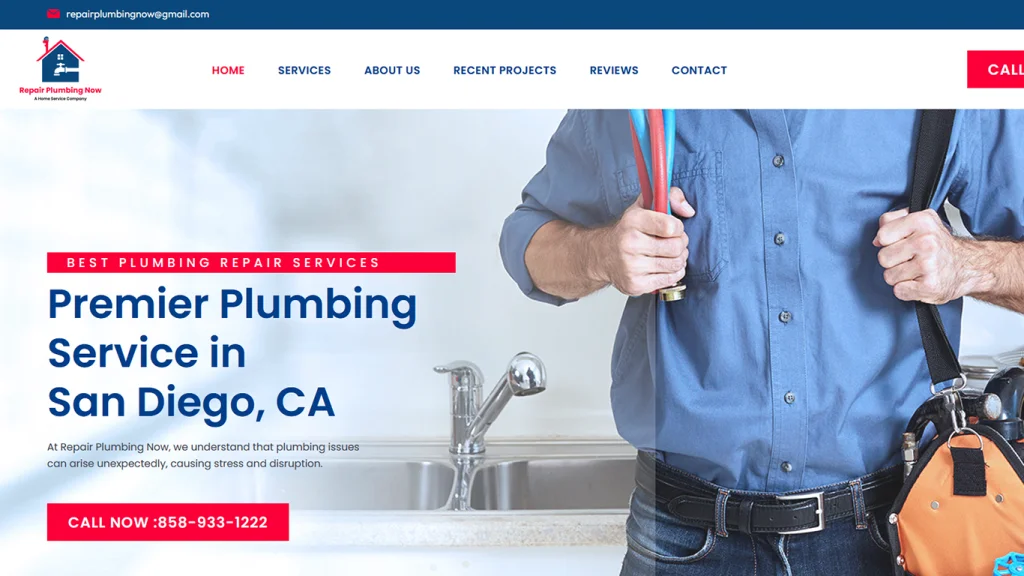

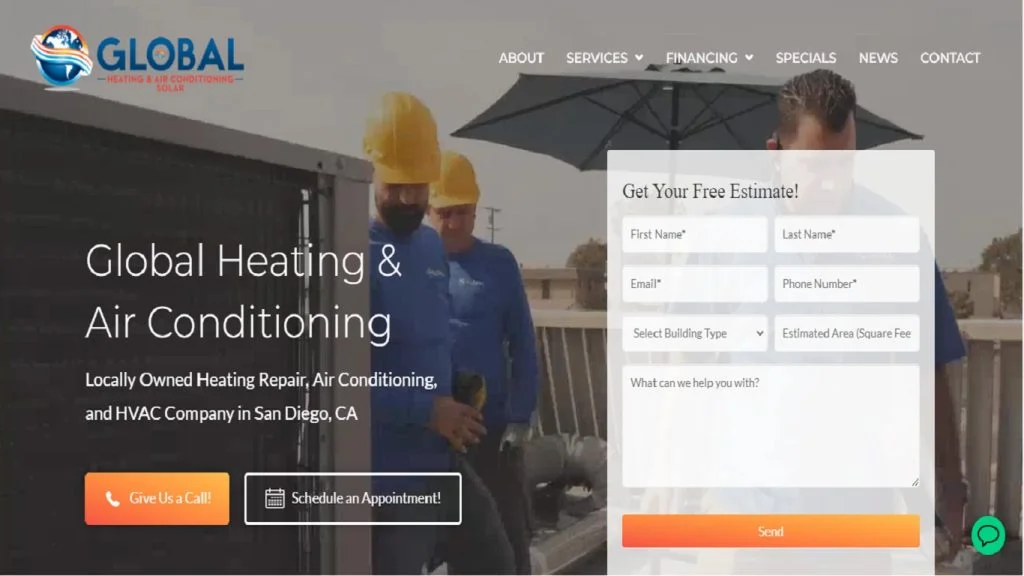

- Designs Tailored for U.S. Business

CRAFTED WEBSITES. FLAWLESS MOBILE APPS. SOFTWARE ENGINEERING. EXCEPTIONAL RESULTS.

An Award-Winning U.S.-Based Web Design & IT Company

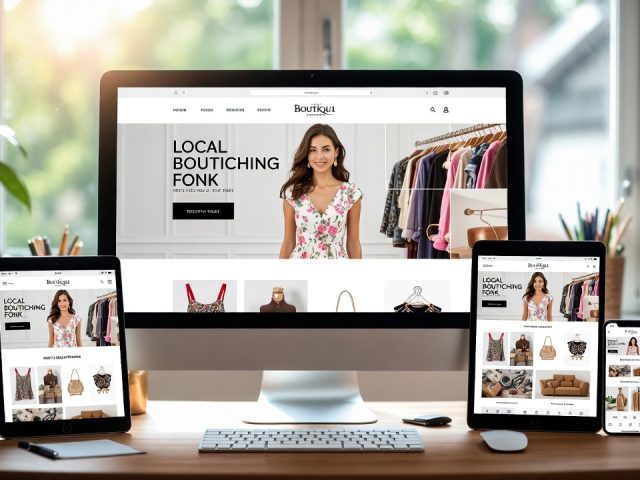

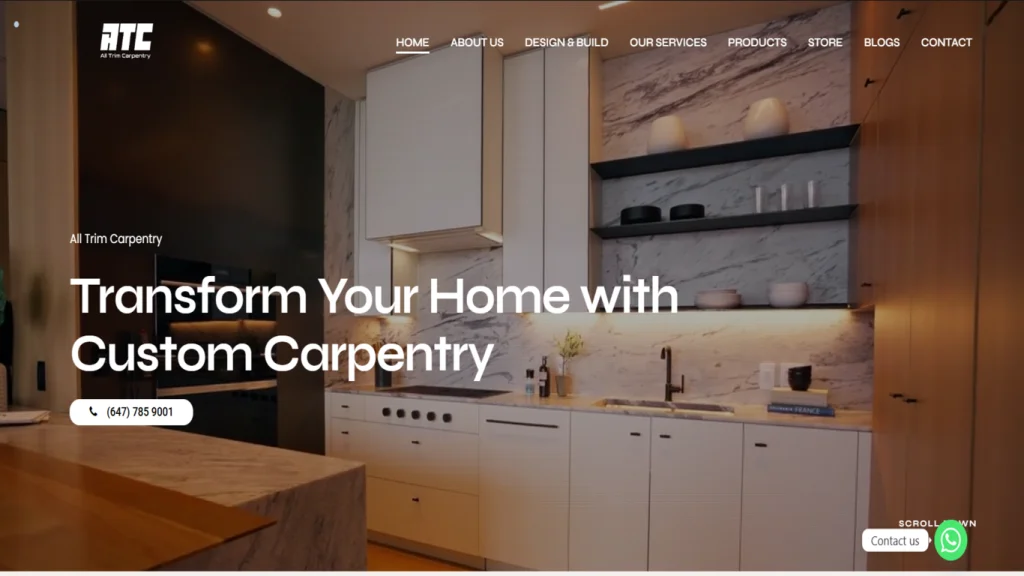

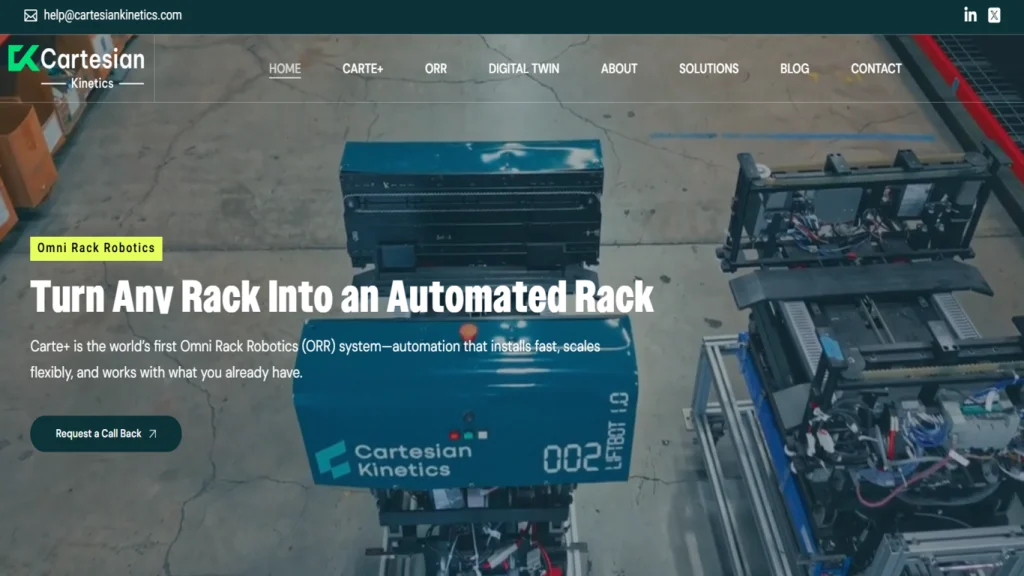

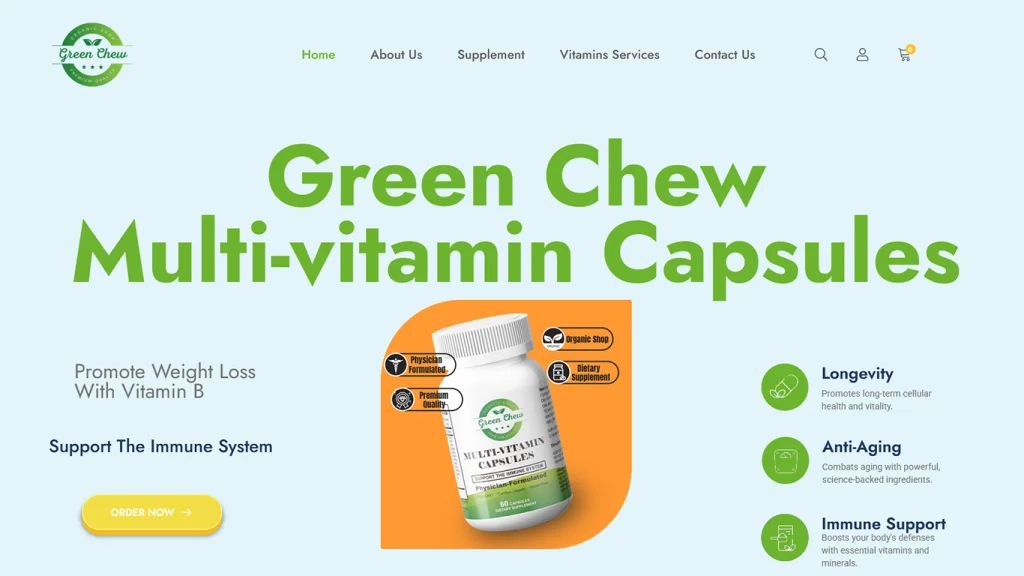

ZeOrbit is a U.S.-based IT company delivering professional web design, custom software development, mobile app solutions, and SEO services for businesses across the United States.

Transforming ideas into captivating realities, we are a dynamic creative team redefining innovation

We specialize in designing, building, launching, and converting. Let's create something truly exceptional together!

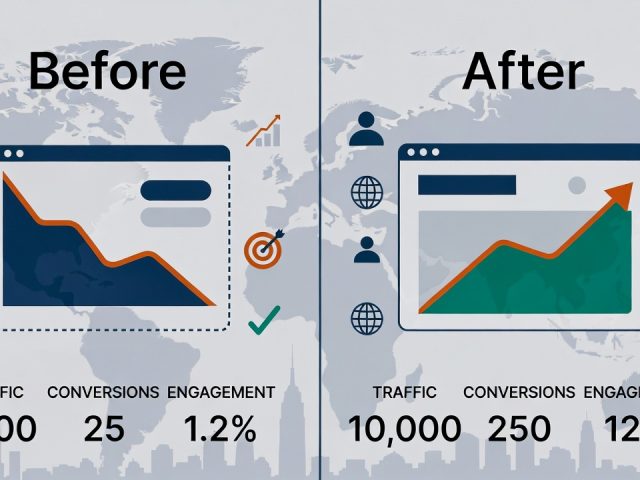

Grow your business search with sleek, professional and customized results

Stay Informed About The Latest News & Trends

Answers to Your Most Asked Questions

1. What services does ZeOrbit offer?

ZeOrbit offers tailored web design and development services, including WordPress & Web Builder Solutions, Web Hosting & Domain services, Ecommerce Store Management, Graphic & Logo Design, Web Research & Data Processing, AI Agent Copilot Development, ML-Powered Development, API Integration Solutions, Mobile Application Development (Android & iOS), Custom Software Engineering, Search Engine Optimization (SEO) & Paid Ads, and Ecommerce Store Optimization.

2. Does ZeOrbit work with small businesses?

Yes. ZeOrbit serves businesses across the United States, including small and mid-sized companies seeking professional websites, mobile apps, and digital solutions.

3. Is ZeOrbit a US-based company?

Yes. ZeOrbit is an award-winning U.S.-based IT company headquartered in San Diego, California that delivers web design, mobile app development, and software solutions to clients nationwide.

4. Does ZeOrbit provide SEO and website maintenance services?

Yes. ZeOrbit provides Search Engine Optimization (SEO) services and paid advertising tactics designed to boost visibility, drive traffic, and maximize conversions as part of its digital solutions.

5. What types of web design solutions does ZeOrbit provide?

ZeOrbit provides expert web design services, including responsive and SEO-friendly websites built with WordPress and other web builder tools, ecommerce store setups, and custom UI/UX designs tailored to business goals.

6. Does ZeOrbit offer mobile app development?

Yes. ZeOrbit offers mobile application development for both Android and iOS platforms, building user-friendly, high-performance apps designed to engage users and scale with business growth.

7. What custom software services does ZeOrbit offer?

ZeOrbit provides custom software engineering, including cloud applications, ERP and CRM platforms, AI-powered systems, and enterprise-grade solutions built to scale business operations.

8. Does ZeOrbit help with ecommerce?

Yes. ZeOrbit offers Ecommerce Store Management and Ecommerce Store Optimization services to enhance performance, boost sales, and create seamless online shopping experiences.

9. What digital marketing services does ZeOrbit provide?

ZeOrbit provides Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and paid advertising services including Local SEO, Nationwide SEO, Blog SEO, Enterprise SEO, and paid campaigns across platforms like Google Ads, Facebook Ads, TikTok Ads, Pinterest Ads, and YouTube Ads.

10. Does ZeOrbit provide AI and machine learning solutions?

Yes. ZeOrbit offers AI Agent Copilot Development and ML-Powered Development to integrate intelligent automation and machine learning into business systems and processes.

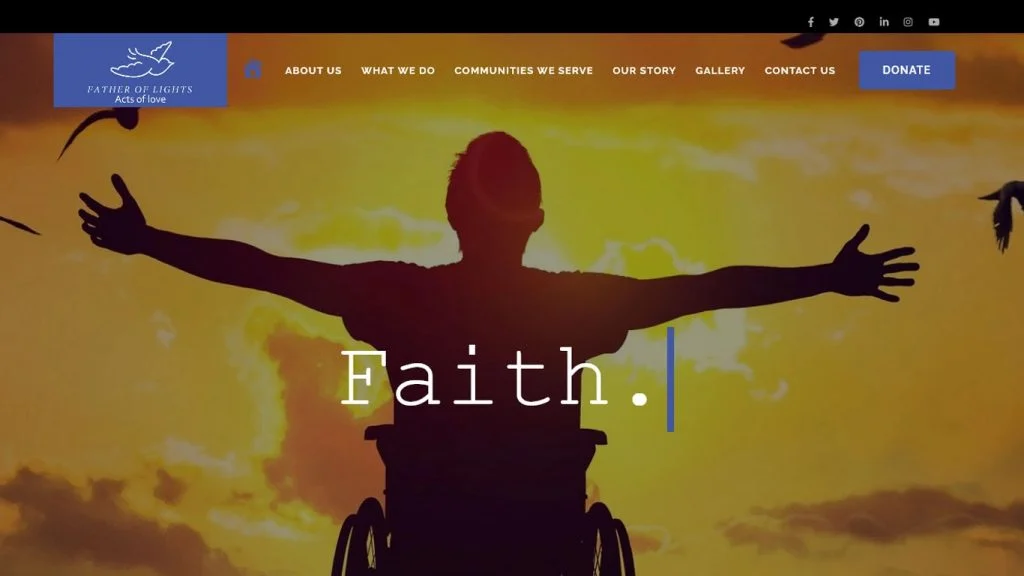

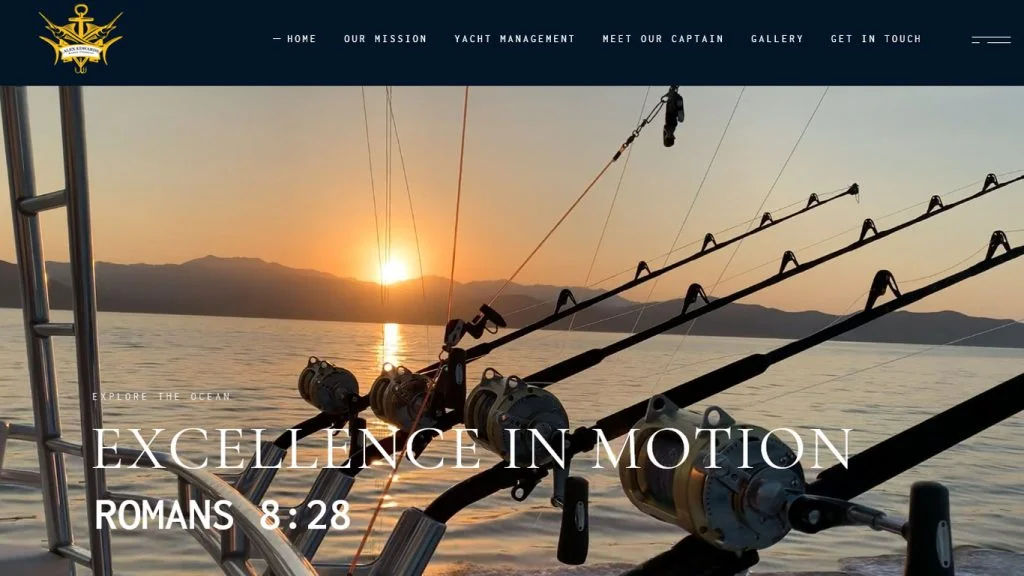

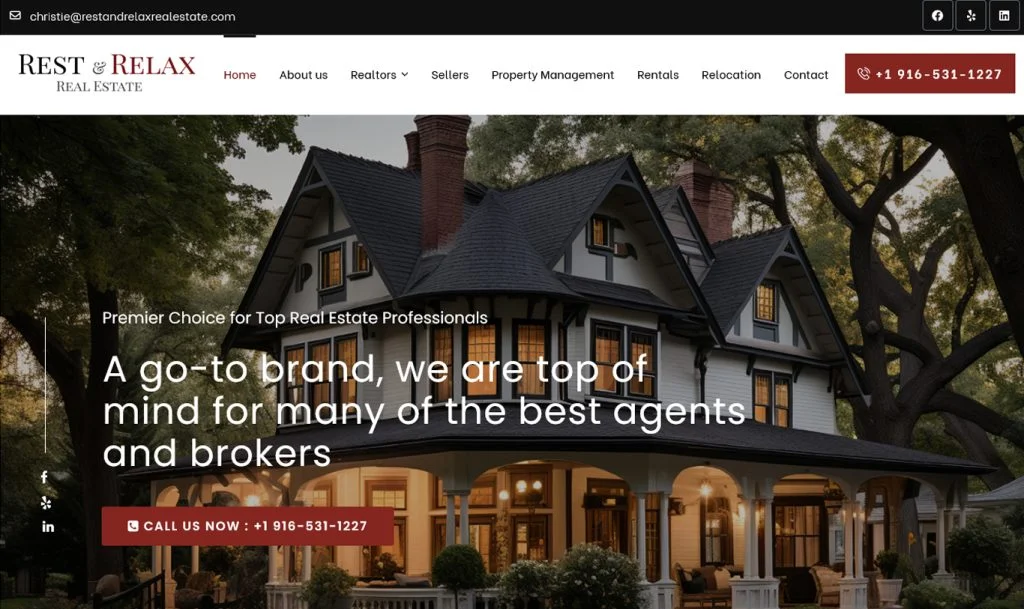

Real feedback, Real results

See why businesses trust ZeOrbit

That same day, I received a call from Sam, who went over everything I needed and discussed pricing, which was very reasonable and fair. Although we encountered some bumps in the road due to issues from the original developer, Sam went above and beyond to ensure we got exactly what we needed. Not only did he complete the requested changes, but he also improved the layout, making the website look even more professional.

Throughout the process, Sam kept in constant communication, keeping us updated every step of the way. We’re incredibly happy to have found Sam and his team, and we will always turn to them for any future improvements to our website. Highly recommend!

Stop thinking, and just trust the process! You won't be disappointed with ZeOrbit.

If you need anything from web design to SEO, they are the go to.